Since it’s summer, most of my free time is devoted to the old “honey-do” list and I have been lax in both blogging and genealogy. I haven’t been as energized as I would like, so I was thrilled to receive this email from a blog reader:

I have been looking into Genealogy recently in St Croix and stumbled across your blog that is probably the most informative thing I have found.Well James, I wanted to give you something to help for your trip. While I certainly didn’t do an exhaustive research job since time is short, I think I found some things that will help your search in St Croix considerably.

I have been looking into a little bit a family mystery. We have not known much about my Great grandfathers Brother (I guess my great -great uncle). Only that he left Denmark and died in the Caribbean. Since I last looked into it a few years back there was not much available on the internet. A couple of seeks ago, I tried again and found quite a bit. His Gravestone on find a grave (his name is Jacob Sorensen). He died a shoemaker in 1874 after at least 25 years on the island. I am not sure how common it was for soldiers to stay on during the Danish period

What I have been able to find through census records, Visha and Ancestry, is that he was married (something that we did not know). I would like to find the marriage license. I would also like to find any christening records (to see if there are any distant cousins out there).

What I also find intriguing is that I believe his wife (Elizabeth Block)would have been descended from Slaves because her mother's name was Ancilla Benners. I have read that Ancilla means Slave girl in Latin. I would love to find out more about them.

The reason I am writing is that I will be going to St Croix for a few days in a couple of weeks. It is a family trip but I am hoping I will have a little time to do some research. I live in Salt Lake City so I do have access to resources but I am wondering if you might have any suggestions on where I might be able to visit in St Croix to find a little bit more about my relatives.

Sorry for the long e-mail. thanks James

Jacob Sorensen

Jacob Sorensen (b. 1822) appears in the St Croix census in Frederiksted, unmarried in 1860 and married to Elizabeth Sorensen in 1870. Before 1860 there are a couple of Sorensen entries who may be Jacob, but it isn’t clear. In 1855, a man simply named “Sorensen”, born 1822, appears as an overseer at Cotton Valley. In the 1857 census there is a Jacob Sorensen in Christiansted and a J Sorensen at Estate Prosperity. Both were born in Denmark in either 1822 or 1823. Any of these could be our Jacob, but it isn’t clear. He is buried in the Holy Trinity Lutheran cemetery in Frederiksted and his tombstone states his dates as b. 11 Apr 1823, d. 31 Jan 1874, age 50 [find-a-grave]. According to the 1870 census, he owned the property at 28 Queens St, Frederiksted. Since he owned property a search of the St Croix Matriculs (NARA M-1884) should tell us when he bought the house and what happened to it after he died.

|

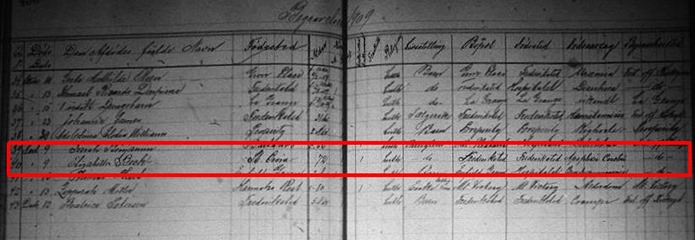

| Detail of 1862 Matricul showing 28 Queen's St |

Elizabeth Block

In the 1870 census, Jacob, 48, and Elizabeth, 31, are listed as “gift”, Danish for “married”. Another household member, Ancilla Benners, 50, assumed to be Elizabeth’s mother, is listed as “ikke gift” or “not married”. In the 1860 census, Elizabeth Block is listed with Jacob, as his “housekeeper”. “Housekeeper” was a common term referring typically to mullatto concubines, so she was probably of mixed race. There was a large age difference between Jacob and Elizabeth (17 years). In fact, Elizabeth’s mother, Ancilla, at 42 was only 2 or 3 years older than Jacob. Further, in the 1860 census, Elizabeth and Ancilla are listed as Catholic. Elizabeth was Lutheran in 1870 so she probably converted before her marriage to Jacob, sometime between 1860 and 1870. The FHL microfilms for the Frederiksted Lutheran church start in 1872, so I was not able to find a marriage record. The NARA M-1884 rolls have some church records, but they are far from complete for this time period. I have also found no mention of a child from the couple.Elizabeth Block/Sorensen and her mother Ancilla disappear from the census at the same time Jacob does, so the question arises “where did they go”? Jacob, of course, dies in 1874 so we know where he went. Travel outside the islands wasn’t very easy for common people in the 1870s, so it seemed likely that they didn’t go anywhere. If that was the case, then perhaps Elizabeth remarried by 1880. To find her I queried my census database, filtering down as much as I could. In 1880 there were 495 Elizabeths [incl variations], 23 who were born between 1838 and 1840. 19 were born in St Croix. 10 were either married or widowed. Only 1 was also Lutheran, Elizabeth Beck. Now, it’s possible that Elizabeth changed her religion again, but multiple religion changes were uncommon and with only one target I figured I’d check it out.

Elizabeth and Frank Edward (Frantz Edvard) Beck appear in the 1880 census in Frederiksted, living at 14 King St. The census says that Frank Edward was born in Elsinore, Denmark and was about a year older than Elizabeth. His is listed as a “painter”, but it doesn’t say whether he painted portraits or buildings. The Denmark Births and Christenings 1631-1900s database on Ancestry.com lists a Frantz Edvard Beck born 21 Oct 1838 and christened 12 Apr 1839 in St Marie, Elsinore, Frederiksborg, Denmark. He was the son of Jorgen Beck and Emilie Wilhelmi. This is probably the same person.

Of course, the only reason we can connect Frantz Edvard and Elizabeth Beck to Elizabeth Sorensen is by elimination. But there’s another reason. Remember above when I discussed what happened to Jacob’s house? In 1876 ownership transferred to Edward Beck. Coincidence?

Since Jacob died in January 1874 and the house transferred to Edward by October 1876, perhaps Elizabeth and Edward were married during this time. Fortunately, the FHL microfilm 300997 contains the Frederiksted Lutheran records from 1872-1908. A quick search of this roll produced a marriage record. Sadly, the date wasn’t recorded, but it is the only entry from 1875. It shows that Elizabeth Beck was indeed Elizabeth Sorensen, and that she and Frank Edward were married that year.

In the 1890 census, Elizabeth Beck is listed as a widow, so Frank Edward died sometime between 1880 and 1890. I have not located a death record. Elizabeth also appears as a widow in the 1901 census, at 55 Kings St in Frederiksted, age 61. She doesn’t appear in the 1911 census.

The NARA M-1884 collection only has Frederiksted Death records from 1879-1889, so they weren't very much help in locating Elizabeth’s death. Fortunately, the Lutheran church records on FHL 300997 do list some deaths and I found her death record. Elizabeth Beck died 9 Nov 1909 in Frederiksted, age 72. Her cause of death is listed as “Apoplexia Cerebri”, Cerebral Apoplexy, basically a stroke. She was buried in the churchyard, although there is no tombstone recorded at Find-a-Grave.

Ancilla Benners

Ancilla appears to be Elizabeth’s mother. Census records say she was born in St Croix about 1818. While she was born there she doesn’t appear in the census until 1850. She is listed as unmarried, so it isn’t likely she had a different surname prior to that.While James’ comment that the name “Ancilla” is Latin for “slave girl” or “handmaid” is interesting, it doesn’t really mean that a person was a slave. It was a very common name used by Catholic nuns who considered themselves “Ancilla Dei” or “God’s handmaid”. Many sisters took the name Ancilla when they took their vows and the name had some small popularity. The 1850 census shows 28 Ancillas on St Croix. Based on the name, it isn’t necessarily the case that Ancilla was a slave, but she certainly could have been.

Since Elizabeth was listed as “housekeeper” in 1860 with Jacob, it seems likely that she was mixed race, and also likely that her mother Ancilla was at lest mixed as well. If she was a free woman, she should have appeared in the 1831 Free Colored Census, probably as a child of 13 years. A thorough search of the NARA M-1883 Register of Free Black Children showed no Ancilla Benners, either in Frederiksted or in any of the Estates. A check of the Christiansted list didn’t show anything either. For good measure I also checked the Free Black Women list, which lists women over 16 years. No entry for an Ancilla Benners. This negative evidence suggests that perhaps Ancilla wasn’t free.

When the slaves were emancipated in 1848, many took surnames and began appearing with their new surnames in the next census, 1850. There were a great many names who appear for the first time in 1850 because of this. Since I couldn’t locate Ancilla Benners or her daughter Elizabeth in any census before 1850, I went back to my database and searched the census for anyone named Ancilla (or Ancila, Ancela, Anciletta), (178 records across all years). When I narrowed my search to only those born between 1817 and 1820 I found 7 records. Each from a different year. Entirely consistent with entries for a single person. 5 entries were for Ancilla Benners (1850-1870) and two for a woman simply named “Ancilla”, in 1841 and 1846. Ancilla was a slave at Estate St Georges Hill, in West End, Frederiksted Jurisdiction. No other Ancillas appeared with the correct age. It seems very likely that the slave girl Ancilla and Ancilla Benners was the same woman.

If the slave Ancilla was indeed Ancilla Benners, her daughter Elizabeth should appear in both the 1841 and 1846 census as well in close proximity to her mother. Elizabeth would have been age 1 or 2 in 1841 and 6 or 7 in 1846. An inspection of the census pages shows that, indeed, there is a girl of about the right age, listed as “Betty” in both the 1841 (age 1) and 1846 (age 5) census. The 1846 census also shows that Ancilla had two children and temptingly lists a 7 year old Isabella. I hesitate to conclude that Isabella is the other child because she is listed as Anglican (English Church). It is possible that Isabella was not her daughter since both Ancilla and Elizabeth were Catholic. While it is a possibility, I’m not yet convinced that Isabella was Elizabeth’s sister.

So it would appear that Ancilla was born a slave, possibly at St Georges Hill, and had two children, including Elizabeth. These children were also enslaved. At least one, Elizabeth, survived and she and her mother were probably emancipated in 1848, at which time they took surnames Benners and Block. Whether these surnames were father’s names is completely unknown. I looked through the emancipation records in NARA M-1883 to see if I could find them, but haven’t been able to find them at St Georges Hill or elsewhere (although I didn’t do a thorough search over the whole island). Without some further piece of information it may be difficult to determine where they may have been around 1848.

Ancilla lived with Elizabeth and her husbands, probably until her death. Since she appeared in the 1870 census but not the 1880, she must have died between these dates. I searched for a death record for Ancilla, but the Frederiksted death records in NARA M-1884 don’t start until 1875. I didn’t find her between 1875 and October 1880 (the date of the 1880 census), so the negative evidence suggests she died between October 1870 and January 1874. There may be a death record in the Catholic church, as the census records list her as Catholic even when her daughter became Lutheran.

Next Steps

So, where should James look next? Since he is going to St Croix this week, he definitely needs to set aside some time and visit the library at Whim. While there he should look for:- Baptism Records – I have not located any baptisms. Both Ancilla and Elizabeth were baptized Catholic so look for Catholic slave baptisms around 1818-1819 for Ancilla and 1838-1841 for Elizabeth (possibly called Betty or Betsy). Another possible project is to scan through the Lutheran baptisms from 1860-1880 to see if Elizabeth had any children who may have been born and died before a census.

- Confirmation Records – It was common when people converted to the Lutheran faith prior to a marriage that they were baptized (if they had not been previously baptized Christian) or Confirmed Lutheran (if they had). If the Frederiksted Lutheran Church has Confirmation records for 1860-1870 you may find Elizabeth Block’s confirmation, probably close to her marriage. It may show her father’s name (although probably not).

- Marriage Records – The Lutheran records may show a marriage sometime between 1860-1870 for Elizabeth Block and Jacob Sorensen. This may show Jacob’s parents, and the witnesses may show a relative on the island. It’s possible that it will help identify where he was from and you may use that information there to track him back in Denmark. The census only states his birth place as “Jylland, Denmark” which is Jutland, the peninsular part of Denmark (not including the islands). There are several counties there. If you find marriage licenses, let me know as I have not discovered any of them. Most marriages were by banns, not licenses.

- Death Records – Death records are much harder to find but look in the Lutheran church for Jacob (1874) and Frantz Edvard (1880-1890). The FHL microfilm doesn’t have death records for 1872-1908. Look for the Catholic church for Ancillas death, probably 1871-1875, possibly later but probably before 1880.

- Emancipation Records – Records of emancipations were made in 1848 and a mother-daughter pair of Ancilla/Elizabeth might appear. These are in the NARA collection M-1883 but if there are other records at Whim, check those.

- Passenger Lists – I doubt much will surface as the Passenger lists to St Croix in the Danish Archive (Rigsarkivet) in Copenhagen only go to 1847. No Sorensens appear in the 1850 census.

- Probate Records – Probate records were rare in Denmark and the colonies for all but the aristocracy. Denmark had very clear inheritance laws that made wills unnecessary for most people. Most probate records are from Estate owners and major merchants. It seems unlikely that Jacob or Frantz left wills. Of course, it never hurts to check if you can find them. Ask if there are any records at Whim. I believe most are either in Copenhagen or College Park, and none are microfilmed.

Other Things

- Definitely visit the homesteads. 28 Queen St in Frederiksted. I would think that visiting this location is mandatory, although any structure there today (if there is a structure there today) is probably not the original house. Much of Frederiksted was destroyed in the Fireburn of 1878. Worth a picture anyway.

- Since Ancilla and Elizabeth were slaves at St Georges Hill, see if you can figure out where the plantation was. The wonderful folks at Whim will help you. Ask if they have any good maps.

- Also, try to locate any residences in Frederiksted where your family may have lived. I did that for my family in Christiansted and it really made me look at the town in a different light.

- Don’t forget to spend quality time on the beach. And remember your sunblock!

David, it's nice that you were able to help James with his genealogical quest. But as a seasoned researcher descended from both the Enslaved and the Enslavers in the Danish West Indies, I am utterly appalled by the sweeping generalizations you tend offer when interpreting records pertaining to St. Croix and Danish West Indian society. Your first troubling comment is the condescending notion that "housekeeper" means mulatto concubine. You don't know that as fact. That is your OPINION and since you claim you are a scientist, you should state it as such. The second disturbing comment is your assumption that the enslaved peoples on St. Croix didn't have surnames and only took surnames after Emancipation in 1848. Again, this a rather narrow-minded opinion. In fact, many of the enslaved had surnames. It would never occur to you that their enslavers didn't ascribe importance to the surnames of enslaved people and therefore often omitted those surnames in documentation. When you conjecture and opine, your unsuspecting, uniniated readers take your comments as fact. Frankly, some of your generalizations are way off the mark. Consequently your credibility suffers with those of us who know better. I can't imagine that'd you would intentionally want to seem insensitive. Stick to the facts and scientific analysis.

ReplyDeleteIncidentally, here are a couple of facts: In the 1850 Census, Ancilla Benners and Elizabeth Blick[Block] were residents at No. 62 Prince Street, Frederiksted. Ancilla, age 32 and a seamstress, was listed as the mother of Elizabeth, age 10. Both were Roman Catholic. In church records I found Ancilla resident at St. George's Hill. Elizabeth's date of birth is not shown, but she was baptized in the Frederiksted Roman Catholic Church on February 9th, 1840.

James, in order to make the most of your research time, I suggest you make an appointment before visiting Whim Library and Archives. Have an enjoyable vacation.

Ricki

Ricki,

DeleteThere is sufficient evidence in the historical record that European men who wanted to marry women of African ancestry in the Danish West Indies suffered undue pressure either from church officials, family members, or even society as a whole through social ostracism. Many men simply could not cope with the situation. In an age where there was no TV, no internet, and no Facebook or chat rooms to while away the hours, the threat of being socially ostracized for marrying outside of one's endogamous social group was a pretty powerful weapon. The Danish writer, Lucie Horlyk, details these tragic circumstances in her short story "Nana Judith". In the story, a Scotsman falls in love with Judith, a woman of uncertain heritage, but can never properly marry her in the church because of bullying and "guilting" from church officials. The story details his descent into alcoholism and an early death because of the social ostracism he suffered as a result. On his deathbed, his chief regret was never being able to properly raise Nana Judith's status from that of "housekeeper" to wife. Incidentally, the daughter he had with Nana Judith was able to break free of society's barriers and marry properly, so the story ultimately had a happy ending.

The whole reason for education is so that people can make educated guesses and form educated opinions. I have been following David's blog since its inception and have found his opinions, conclusions, and compassion for the subject to be of the highest possible caliber. If in your research you have found evidence that contradicts David's conclusions, then perhaps you should write a guest blog to present your findings.

-Rachel

Ricki,

ReplyDeleteYou are quite right to call me on anything I state that is not "common knowledge", and your points are no exception. I assure you that my statements are not my theories; they are the result of research and have held up to my own experience researching my own family as well as numerous others. My 4th great grandmother, Hester Franklin, a former slave, lived as "housekeeper" with my 4th great grandfather, English-born Joseph Robson from at least 1827 until his death in 1859.

To your points, I don't assume that all housekeepers were freedwomen nor that all freedwomen with white men were "housekeepers", simply that it was a common practice and therefore a possibility. I don't claim that no slaves had surnames nor that all freed slaves took them, simply that some did and it is a possible explanation for someone appearing in a census for the first time as an adult. It is simply good genealogical practice to consider the potential explanations for the evidence seen and look for hints on where to look next.

On the subject of "housekeepers", there is contemporaneous evidence. In the late 1830s, a man named Sylvester Hovey traveled to St Croix on behalf of the American Union for the Relief and Improvement of the Colored Race in Boston and documented the state of slaves and free coloreds in the Caribbean through a series of letters to said organization. His first-hand accounts are collected in "Letters from the West Indies: Relating Especially to the Danish Island St Croix", published in 1838 and available on Google Books. Hovey writes on pages 33 and 34 discussing the treatment and social status of free coloreds on St Croix:

"The least iniquitous and disgusting shape, in which it [racial inequity] appears, is the practice of taking colored or black women as housekeepers; but who are, to all intents and purposes, wives, except in name and respect. The custom is very general among managers and overseers of estates; and is by no means unknown in the highest places of influence and authority."

That's not my only reference. In "Slave Society in the Danish West Indies", by Nevelle Hall, John's Hopkins University Press 1992, the author writes on page 151 about this very term in his discussion of the practice of white men taking a "concubine" [a term he uses to refer to cohabitation outside of marriage, a common West Indies practice] of freedwomen:

"By the nineteenth century, these same classes [i.e., Danish official classes] were to become a byword for their relationships with freedwomen "housekeepers" [quote in original]." He goes on to discuss the white/colored relationships stating, "Marriages were out of the question". He notes that apparently lifetime commitments and family life were not. He concludes the paragraph by saying, "In the Danish West Indies, such relationships during the eighteenth century became the "custom of the country," although the arbiters of the convention were exclusively the islands' white males."

Neville Hall is a well-respected authority and until his death in 1986 was a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and General Studies at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus. I spoke with B.W Higman (also at the University) who edited Hill's manuscript for posthumous publication about many aspects of the book. I consider Hall and Higman to be scholars of the highest caliber and together with the first-hand account of Sylvester Hovey to be far superior to any theory I may construct.

From these and my own experience, I feel comfortable claiming that the practice, and term, was common.

Further, I did not conclude that Ancilla was a slave based on this fact, but rather stated that the designation in the census made me consider the possibility. My conclusion, and I state it is still a hypothesis, was based on the fact that all of the census entries for women named Ancilla, born around 1818, are consistent with a single person, at one time listed as a housekeeper and at another time a slave.

ReplyDelete[continued] As for slaves taking surnames, I did not suggest that all freed slaves took surnames, simply that some did. Overall, most do not seem to have taken surnames, at least immediately. In the 1846 census, there are a total of 23,632 entries, 16,071 of which have no surnames. Four years later the islands population had grown very slightly to 23,883 and 13,844 had no surnames. In 1855, out of 22,684 census entries, 10,514 had no surname. While it is certain that some of this is due to births and deaths, the trend is still visible. Further, in my analysis I simply stated that this was a possible explanation, not that everyone did this.

Further evidence of the taking of surnames is provided by Hall on page 148 where he claims that the practice of taking surnames rose to such a level in 1775 that the government included restrictive language in the Ordinance of 1775. Hall states, "[Governor General] Clausen claimed that it had come to his attention that former slaves of both sexes, black as well as mulatto, had taken the names of their former owners and had baptized their children using the same names." He goes on to say that the ordinance "decreed that no free black or mulatto of either sex would thenceforth be allowed such patronymics, unless they used the formula "N.N. manumitted by N.N." Failure to do so was to result in corporal punishment." The practice of choosing surnames was apparently commonplace by 1775 when Governor Clausen addressed the issue. I have found no formula that was used in selecting surnames and so I made the statement that no conclusions could be reached from the surnames "Benners" and "Block" in James' family at this time.

Since I was trying to outline a line of research and not attempting to write a scholarly article, I didn't include any of this in my blog. In trying to put the pieces of our history together, we must necessarily formulate hypotheses and test them. It would be irresponsible to draw a conclusion from common practices, but it's those hypotheses that give us something to test, somewhere to look. I believe that my analysis is correct and I arrived at it by sound "scientific" principles, founded in facts and evidence.

That said, I have no problem at all with you, or any reader, challenging anything I say. It is only through peer review that research can be kept honest and hidden biases can be removed. I am saddened that you made some very unfortunate assumptions about my motivation, however. I assure you, I have no such feelings.

David:

ReplyDeleteYour professional manner in responding to critiques is commendable. I've learned a great deal from your research. Please continue the good work.

ERS

I just came across this interesting blog post by La Vaughn Belle, a visual artist and documentary filmmaker who interviewed Gerard Emanuel, a retired St. Croix history teacher and a social sciences professor. In the interview they discussed "the "untidiness" of slavery and its legacy, how race dynamics were not as neat and clear-cut as some might want to envision. Freed Blacks might have owned slaves. Whites masters might have fallen in love with their slaves. Freed Colored women might have used their sexuality to advance their position in society. And White Danes might have also exploited them. There were so many unanswered questions: What was the relationship between the Free Black community and the still enslaved community? Did the Free community see themselves as advocates for the enslaved or did they only seek out to create a way for themselves to have more rights and be more equal to Whites. Who is this figure of the "Housekeeper"? Was this simply a legal term to try to legitimize a romantic relationship with Black and Colored women? Were these women exploited or did they actively seek out these relationships with Danish men? How did the enslaved see the Freed Blacks? Did they aspire to be like them? Or did they see maroonage as a more desirable option considering the restrictions that Freed Blacks were also placed under?"

ReplyDeleteI would encourage everyone to read the blog. This is a topic worth exploring.

http://thehousethatfreedombuilt.blogspot.com/2013/07/interview-gerard-emanuel-retired.html

--Rachel

Thannks for writing this

ReplyDelete